TL;DR

An attacker can identify which streaming video a targeted user is watching on services such as Netflix and Youtube. The attack can be done remotely over the Internet, and requires only that the user (or even someone else on the same local network) visits a suitably-crafted website from their web browser.

Paper

- Roei Schuster, Vitaly Shmatikov, Eran Tromer, Beauty and the Burst: Remote Identification of Encrypted Video Streams, proc. USENIX Security 2017, to appear

- First published on 9 April 2017. Latest version (12 July 2017): [PDF]

Overview

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and so, to garner what we behold is to glean what we cherish. Today, much of what we behold is video content streamed from the Internet, and our choice of movies, TV shows, news clips and social media videos reveals much about our personality, preferences, socioeconomics, and mood. A bevy of parties seek to exploit this information: whether for monetization by advertisers, insurers, and price-differentiating vendors, or to castigate those who access undesired information.

Encryption of Internet traffic places a hurdle to such monitoring, but it is known that traffic analysis, inspecting merely the size and timing of network traffic, often allows deduction about the traffic's content. How effective is traffic analysis for encrypted streamed videos, and how feasible is it for potential adversaries?

We demonstrate highly effective techniques for how a an attacker can deduce what of videos are watched by a targeted user on streaming services such as Netflix and Youtube, from direct and indirect measurement of encrypted network traffic. We consider three classes of attack scenarios:

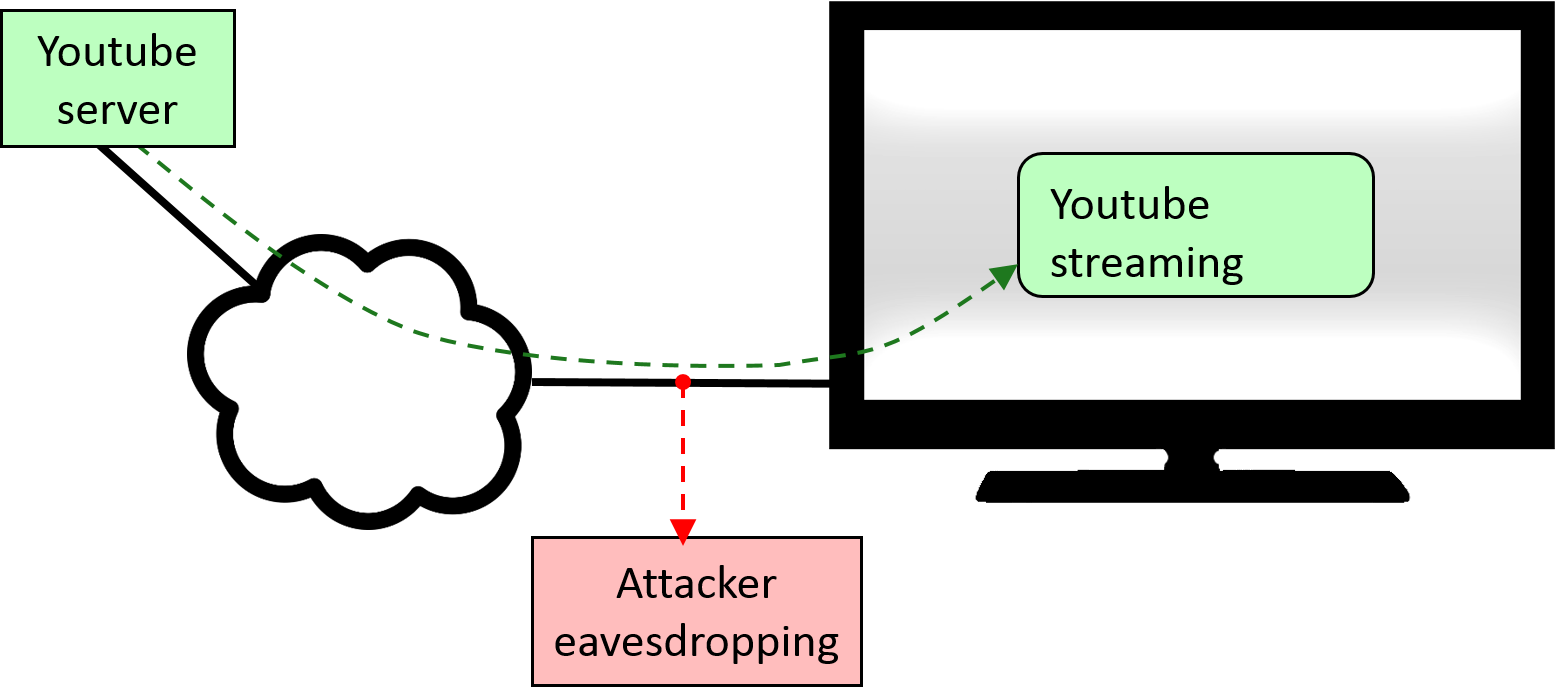

On-path attacks, the easiest scenario, involve an adversary who can passively monitor the user's traffic. This includes Internet Service Providers, malicious Wi-Fi access points, proxies, VPNs, routers, and taps on network connections. These have full and accurate visibility of individual packets, and using our techniques, they can identify which encrypted videos are watched by users of the network links they monitor.

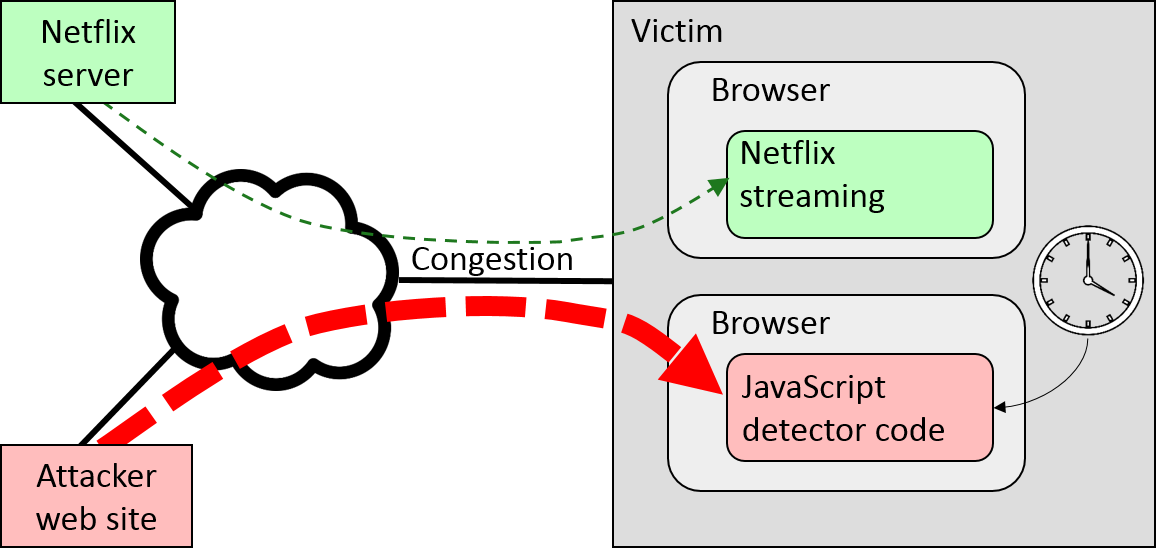

Cross-site attacks, where the only access the attacker has is the ability to send JavaScript code for execution by the victim's browser (see first figure below). This is a particularly dangerous scenario: untrusted JavaScript code from operators who have commercial interest in user viewing habits is, nowadays, ubiquitous. Browsers supposedly execute such JavaScript code in a confined standbox, to prevent it from gleaning private information. We show that this confinement fails: the attacker can measure the network traffic associated with video streaming, using a side channel: he floods the network link with his own data and measures the resulting fluctuations in the network congestion. After a few minutes of such measurement, the video can be deduced.

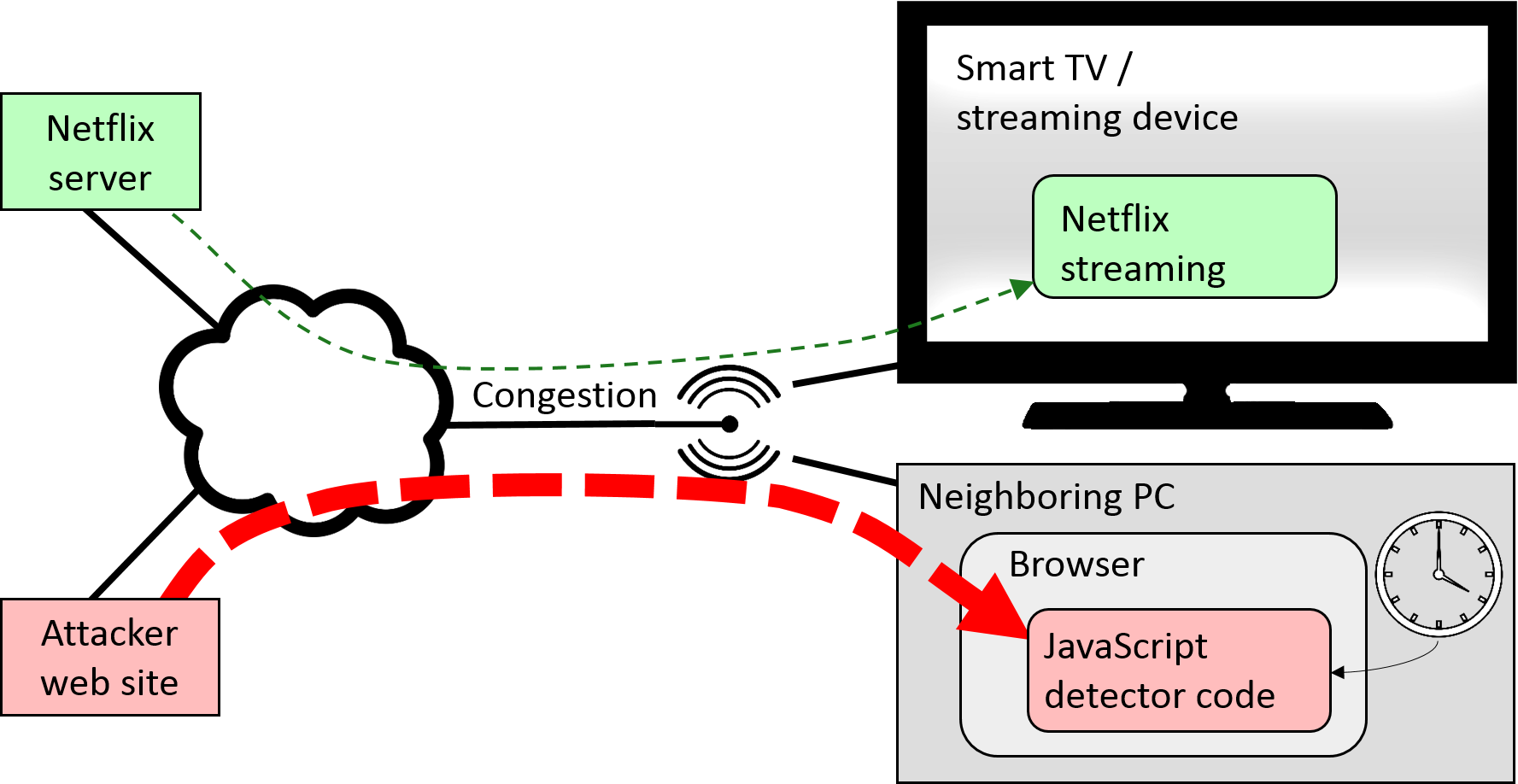

Cross-device attacks are an even stronger way to identify the traffic patterns: for example, a user watching Netflix on his TV may be attacked by JavaScript code which happens to run in a browser on some PC in the same local network (see second figure below). This attack, too, relies on inducing and measuring congestion on the network link that is common to the streaming device and the neighboring PC.

To identify videos based on the recorded traffic patterns, we employ "deep learning" techniques using artificial neural networks, trained them on movies from several leading streaming services. The training of the neural-network video classifier needs to be done on videos streamed to a streaming device (or software) similar to the target user, and connected to a similar streaming server. When trained to recognize dozens of titles, our YouTube detector has 0 false positives with 0.988 recall, while the Netflix detector has a false positive rate of 0.0005 with 0.93 recall.

Q&A

Q1: What services are vulnerable?

We tested our detectors on four services: Netflix, YouTube, Amazon Video,

and Vimeo. We found all of them to be vulnerable to our

video-identification techniques.

Generally, any streaming service using

the popular MPEG-DASH standard for streaming over HTTP(S), and specifically the MPEG-DASH content segmentation, is likely to cause an exploitable

information leak. The inherent reason is discussed in Q6

below. All four services we tested are therefore vulnerable: YouTube directly follows the standard, while Amazon Video, Netflix, and Vimeo use very close variants which adopt its leaky use of content segmentation.

Q2: How could it be exploited?

Malicious Wi-Fi access points, proxies, routers, enterprise or national network moderators, and ISPs are all able to gain insight on user viewing habits by analyzing encrypted application layer traffic frames.

Censhorship gateways can use this information to block monitored content even under encryption.

All providers of web content accessed by the user, including advertisers, analytics providers and social networks, can also compromise the user's viewing privacy, by leveraging our side-channel attack.

Q3: How is VBR related to video content?

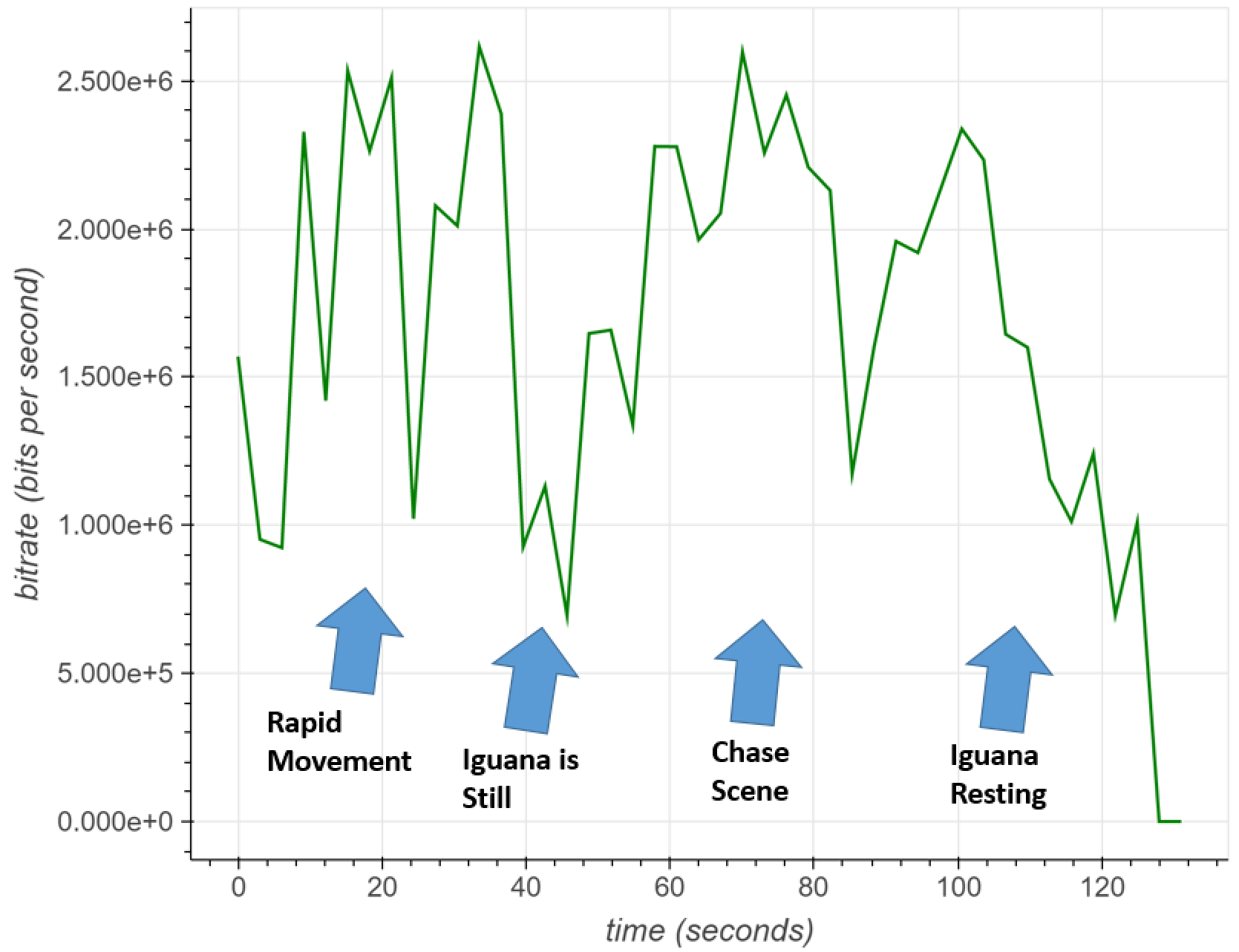

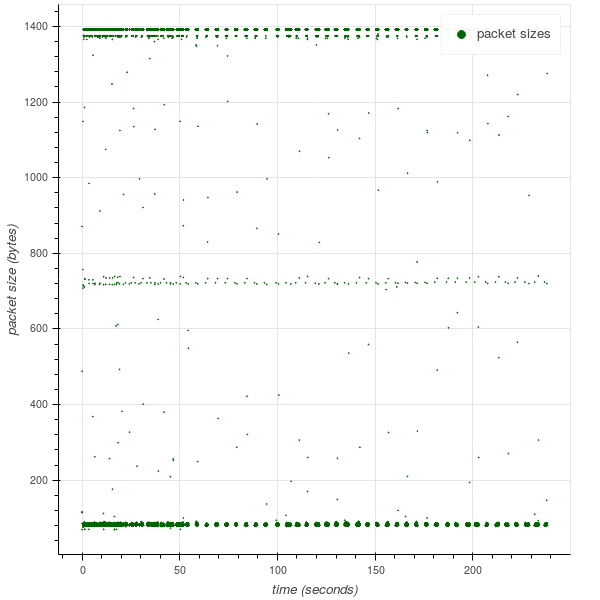

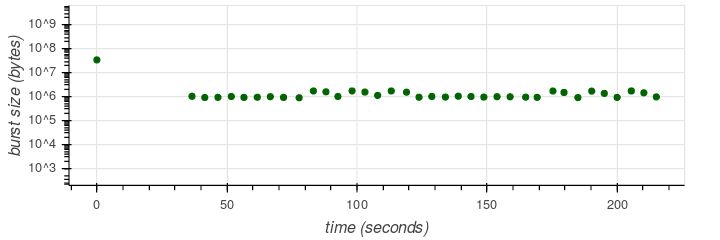

Compression using variable-bitrate (VBR) encoding is designed to use the minimum amount of data needed to represent a scene at a given perceptual quality. This highly dependent on the video content. For example, highly eventful action-scenes, such as the one in the video Iguana vs. Snakes, require a high bitrate to represent. This is easily seen in the diagram below, depicting the bit rate fluctuations as the video progresses through different scenes.

Q4: What are bursts in traffic pattern, and how are they related to video content?

In MPEG-DASH streaming, videos on the server are divided into segments that the video-player client then fetches. This results in an on/off, bursty traffic pattern during video streaming.

To demonstrate how this relates to actual content, we used the aforementioned Iguana video: a high-bitrate portion of the video interleaved with a low-bitrate one. The left-hand figure shows packet sizes along the time axis; observe the pattern of buffering followed by the on/off steady state. The right-hand figure shows the size of traffic bursts; the first, largest burst is the buffer.

Q5: How does the video identification work?

The problem of automatically matching a burst series to a video title can be addressed by various machine learning algorithms. For example, it is natural to represent a streaming session as a series of burst sizes, and directly search for correlations with the bursts in other sessions to check if the same content was streamed. However, we require an approach that is very robust to the presence of noise and distortion that are introduced by encrypted protocol layers, by the indirect measurement using side channels attack channel (such as in our JavaScript-based attack), or by the streaming service as a mitigation.

Deep neural networks (artificial neural networks with multiple layers) have been recently proven highly effective in many pattern detection problems. Their design principles allow them to learn and utilize what is regarded as abstractions: concepts that are intuitive and easy to agree on for humans, yet hard to formally express. As a result, deep learning algorithms are basis for drastic improvements in many problems in vision, image processing, speech recognition, natural language processing, and others. We constructed a deep convolutional network architecture that detects videos using features from their traffic. Employing deep learning resulted in an accurate and noise-adaptive detector, effective even when measurements are performed from a side-channel.

Q6: Why does this information leak happen? Can I make it stop?

The root cause of information leaks in video streams is that the amount of information needed to represent a video segment, at a given perceived quality, depends on the content of the segment. For example, a nearly-still nature scene, or a talk show where most of the picture is static, can be compressed to a much smaller size than a fast-paced action scene. Streaming services use Variable Bitrate (VBR) compression schemes that take advantage of this, to reduce the amount of transmitted data. Consequentially, their traffic pattern is data-dependent.

One can eliminate VBR encoding, or slow down the adaptive response to change in video compressibility, but this reduces the compression ratio (hence, raises costs and may cause network congestion and buffering delays in video playback).

The VBR pattern is inherently observable in traffic if the duration of the client's buffered video is close to constant (or, more generally, an affine function of presentation time). Thus, one can try to foil analysis by erratically changing the buffer size, though this too reduces network efficiency and increases chance of buffering delay in video playback.

Q7: Can the attack be detected?

The on-path attack is completely passive; it cannot be detectable, neither by the user nor by network-based monitors.

The off-path attacks, in our experiments, were imperceptible to the viewer being targeted: the streaming playback proceeded without interruption despite the extra traffic induced by the attack. This is because the upstream routers try to fairly allocate the bandwidth among the multiple data streams: in our case, the video and attacker's. Since video streaming typically requires less than half of the available bandwidth, it can still be streamed at the requisite average pace. Moreover, whenever a video segment is transmitted, the routers typically give it a higher dynamic priority (i.e., a "fast pass" to the top of the queue), compared than the attacker's stream which has already used up more than its fair share. The extra traffic induced by the attacker will affect the user's total bandwidth usage, similarly to downloading a large file.

Acknowledgments

Roei Schuster and Eran Tromer are members of the Check Point Institute for Information Security.

This work was supported by the Blavatnik Interdisciplinary Cyber Research Center (ICRC); by the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA) and Army Research Office (ARO) under Contract #W911NF-15-C-0236; by a Google Faculty Research Award; by the Israeli Ministry of Science and Technology; by the Israeli Centers of Research Excellence I-CORE Program (center 4/11); by the Leona M. & Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; and by National Science Foundation awards #CCF-1423306, #CNS-1445424 and #CNS-1612872.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of ARO, DARPA, NSF, the U.S. Government or other sponsors.